Since the inaugural conference in Berlin in 1995 to the most recent gathering in Sharm El-Sheikh in 2022, a series of 27 Conferences of the Parties (COPs) have been convened by world leaders to address climate action and devise strategies for financing its implementation. Conferences of the Parties (COPs) serve as the absolute most significant platforms for deliberating new policy frameworks, scientific findings, and agreements aimed at both adapting to climate change and mitigating its adverse impacts. As the anticipation grows with only 60 days remaining until the 28th COP, scheduled to take place in the United Arab Emirates, speculations are mounting about the potential outcomes and discussions that will transpire during this significant conference.

However, before getting to unpack the strategic priorities of COP 28 as identified by the UAE, a good political and historical contextualization of the issue of climate change is due here.

The manifold nature of Climate change: To what extent is it urgent to act?

The complexity of climate change as an international challenge lies in the very fact that its consequences are not limited to the environment, rather they are interlinked most importantly with health, economic performance and livelihoods, demographics, peace and security. That is why understanding the multifaceted nature of climate change and its profound impacts on various aspects of society is of Paramount significance.

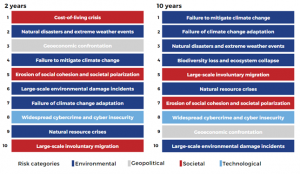

According to the Global Risks Report, in 10 years, 6 out of the 10 most serious risks facing humanity will be environmental in nature. These risks predominantly arise from shortcomings in both mitigating and adapting to climate change, as well as from natural resource crises and the occurrence of extreme weather events that are linked to climate change. Undoubtedly, the depth and breadth of the consequences of and the risks associated to climate change add to the urgency of addressing it, especially as there is a growing international public pressure to do so.

Figure (1): Global risks ranked by severity in the short run (2 years) and the long run (10 years)

The trajectory of the international regime on Climate Change

The momentum around combatting climate change steadily increased on the international stage with countries, international organizations, and a multitude of stakeholders including international experts, civil society organizations, actively convening to address climate action. The primary objective of these gatherings is to facilitate a collaborative platform where these varied stakeholders can collectively contribute their ideas and strategies to combat climate change.

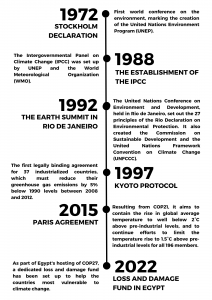

Below are the historic milestones for climate action:

In 1972, the Stockholm Declaration, was the first world conference to centralize the environment as an international policy issue. It launched discussions between developed and developing countries to highlight the impact of environmental crises on many aspects, primarily the economy. This conference marked the creation of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

The UNEP, in cooperation with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) later in 1988. The IPCC is a United Nations intergovernmental body that aims to provide policymakers with scientific information on climate change and the risks it may pose for the world so that they can implement evidence-based adaptation and mitigation policies.

The aforementioned conferences so far have only included government representatives and scientists. It was not until 1992, that for the first time, civil society was included in the climate change dialogue at the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro (also known as the Earth Summit), where a global forum of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) representatives was set up. The Earth Summit gave rise to a new vision of development, “Sustainable Development”, which includes social and environmental aspects as the main pillars of growth. This concept was translated into the 27 principles of the Rio Declaration, which set out principles on environmental protection and building partnerships. It also created new entities such as the Commission on Sustainable Development and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC has now been ratified by 198 countries, and is the entity that organizes the annual “Conference of the Parties (COP)”.

Since its launch in 1995, 27 COPs have been held, and there is a global consensus that two of the most important COPs were Kyoto (COP 3) in 1997 and Paris (COP 21) in 2015. It is mainly because all the environmental treaties mentioned provide general principles of environmental protection, but they are all voluntary and non-binding. However, the first agreement to be binding on a number of its members was the “Kyoto Protocol”, which was adopted in 1997 and came into force in 2005. The Kyoto Protocol was legally binding on 37 industrialized countries, which were required to reduce their GHG emissions by 5% below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012. Then, to renew this commitment, the Doha Amendment was adopted to reduce GHG emissions by 18% below 1990 levels between 2013 and 2020.

Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement resulting from the COP21 held in 2015 was legally binding on all 196 parties, committing to reduce the GHG emissions of all its members. Its main objective is to “contain the increase in global average temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to continue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Figure (2): A brief history of key milestones

If there’s a global consensus on the dangerous consequences of climate change, then why aren’t countries working together enough to tackle it?

Science shows that climate change is detrimental to the planet on all levels, therefore, there is a consensus that an action has to be taken to face it, except a few skeptic voices that still deny the phenomenon. However, there is no consensus between countries on the amount of effort that has to be put in by each country. In fact, from a certain point of view, the imposition of binding rules on developed countries alone is seen by many as only fair and even indispensable for the attainment of climate justice on the states level.

Indeed, historically, developed countries have been the biggest GHG emitters. As a result, many consider it fair to impose more regulations on developed countries, as they are not living up to their promises to protect the interests of developing countries under the non-binding Rio agreement. Consequently, the imposition of regulations on developing countries has been perceived by the latter as a means of hindering their economic growth.

On the other hand, numerous studies have shown that imposing such measures only on a certain number of developed countries could still be not productive as these countries dump their emissions in developing countries. With developing countries having the least stringent rules on GHG emissions, many countries and major corporations have offshored their activities there.

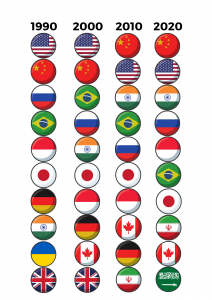

The following figure shows that the top 10 CO2 emitting countries progressively include a greater number of developing countries following data from The Climate Watch platform. For example, the top CO2 emitting country has become China instead of the USA, and countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia have entered the top 10 list.

Figure (3): Top 10 CO2e emitting countries (on a 10-year basis, from 1990 to 2020)

What is on the agenda of COP 28?

Under the slogan “Bringing the world together”, the United Arab Emirates is hosting the next COP. The fact that they are one of the world’s largest producers of fossil fuels has given rise to much controversy. However, the UAE has a strong break-through policies in place fostering climate action; according to UAE Net Zero 2050, the UAE has invested over USD 50 billion in the renewable energy sector and plans to rely on clean energy sources such as solar and nuclear power to reach 14 gigawatts by 2030. In addition, it is the first country in the region to ratify the Paris Agreement, the first to commit to an economy-wide reduction in emissions.

COP 28 Presidency plan of action identifies four main themes as a center of focus; Fast-track the energy, Fix Climate Finance, Focus on nature, people, lives and livelihoods and full inclusivity. Regarding Climate Finance, the president of COP 28, Sultan Al Jaber insisted on the importance of increasing all sorts of funds to be attributed to developing countries as climate change adaptation policies to reach USD 100 Billion. This is an assuring prioritization of the funding issue, and it directly leverages the major success accomplished in COP 27 with the initiation of the loss ad damage fund.

On the other hand, regarding mitigation policies, Al Jaber expressed that implementing the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping temperature levels below 1.5 degrees Celsius is among COP 28’s plans under the “fast-tracking the transition to a low-CO2 world” pillar. This goal has to be enforced by stricter National Determined Contributions (NDCs) by the countries.

The timeless prerequisites of combatting climate change

In conclusion, despite the numerous efforts made by the global community in recent decades, the world is still facing significant challenges in effectively addressing climate change. One of the key obstacles is the lack of coordination and collaboration among countries. Without strong international cooperation, meaningful action to combat climate change remains elusive. It is imperative to establish stricter rules and guidelines for coordination between developed and developing nations, guided by the principles of climate justice. This ensures that all countries have an equal voice and opportunity to contribute to climate action.

In addition, inclusivity here is crucial. It is not solely the responsibility of governments to drive climate action, but also of academics, civil society, and the private sector.

Engaging these diverse stakeholders in inclusive discussions allows for a broader range of perspectives and expertise to be considered, leading to more effective and comprehensive solutions. Furthermore, there is a need for political decision-makers to adopt more binding regulations. These regulations should be clearly articulated in countries’ NDCs. By establishing stronger and more enforceable commitments, countries can demonstrate their dedication to addressing climate change and hold themselves accountable for their actions.

Addressing the challenges to climate action requires a collective effort and a commitment to inclusivity, coordination, and binding regulations. Only through these means can we bridge the gap between intention and tangible results, and work towards a sustainable and resilient future for generations to come.